By Elena Eu

Also on: https://www.elenaeu.com/post/why-are-some-people-naturally-thin-and-others-are-not

Why is it that some people can eat whatever they like and not gain weight? Why is it so difficult to lose weight? Researchers have consistently found that the body's resistance to significant changes in weight are caused by biological safeguards that exist to defend our set point weight. Why is this range different across individuals?

The healthy weight an individual's body aims for is called a set point weight, and like any biological force, and the system works tirelessly to bring his/her body back to a comfortable point (Bacon, 2010). The body's attempt to maintain homeostasis is one of the most fundamental concepts in biology, and this applies to our weight. The mechanisms involved in body weight regulation include physiological, biological, and genetic factors.

Our set point is largely determined by genetics. Using twin studies, researchers have consistently found that “at least 40 % of the variability in BMI” is related to genetic factors involved in the “regulation of food intake and/or volitional activity.” (Ravussin, 2000). Moreover, a 2015 study of over 225,000 individuals found that body fat distribution is a heritable trait, suggesting the overall impact of dieting and exercising on attempts to change one’s weight are limited (Ravussin, 2000).

Why can’t diets and exercise can’t get us out of our set point range physiologically?

On a physical level, dieting prompts the same physiological responses that would result during a famine. Diets interfere with thinking ability, lead to obsessive food thoughts, cause stress, and increase levels of the stress hormone cortisol (Tomiyama, 2008). In high doses, cortisol can cause a multitude of problems including suppressing the immune system, slowing the healing process, speeding up the aging of our cells, elevating blood sugar levels, prompting the body to store fat in the abdomen, as well as weight regain (Tomiyama, 2008).

Exercise plays a significant role in metabolism and preserving muscle mass, however, alone accounts for only a minimal amount of weight-loss in the long-term. It is well accepted that physical activity is one consistent element associated with long-term health, and countless peer-reviewed studies note improvements in heart rate, blood pressure, and cardiovascular health, regardless of whether participants lost or gained weight (Tomiyama, 2013).

One of the reasons why exercise is cited to not bring about major weight loss is that a lot of it is required to “burn off” a significant amount of calories, and many individuals report “indulging in treats” after working out because they feel as though “they’ve earned it” (Tomiyama, 2013). The diet industry promotes cardio as a means to achieve weight loss, however, cardio burns calories - not fat (Tomiyama, 2013). 增肌是有效果的,因为Muscle cells burn more calories than fat cells, so the more muscle built, the more calories are burnt while resting (Tomiyama, 2013).

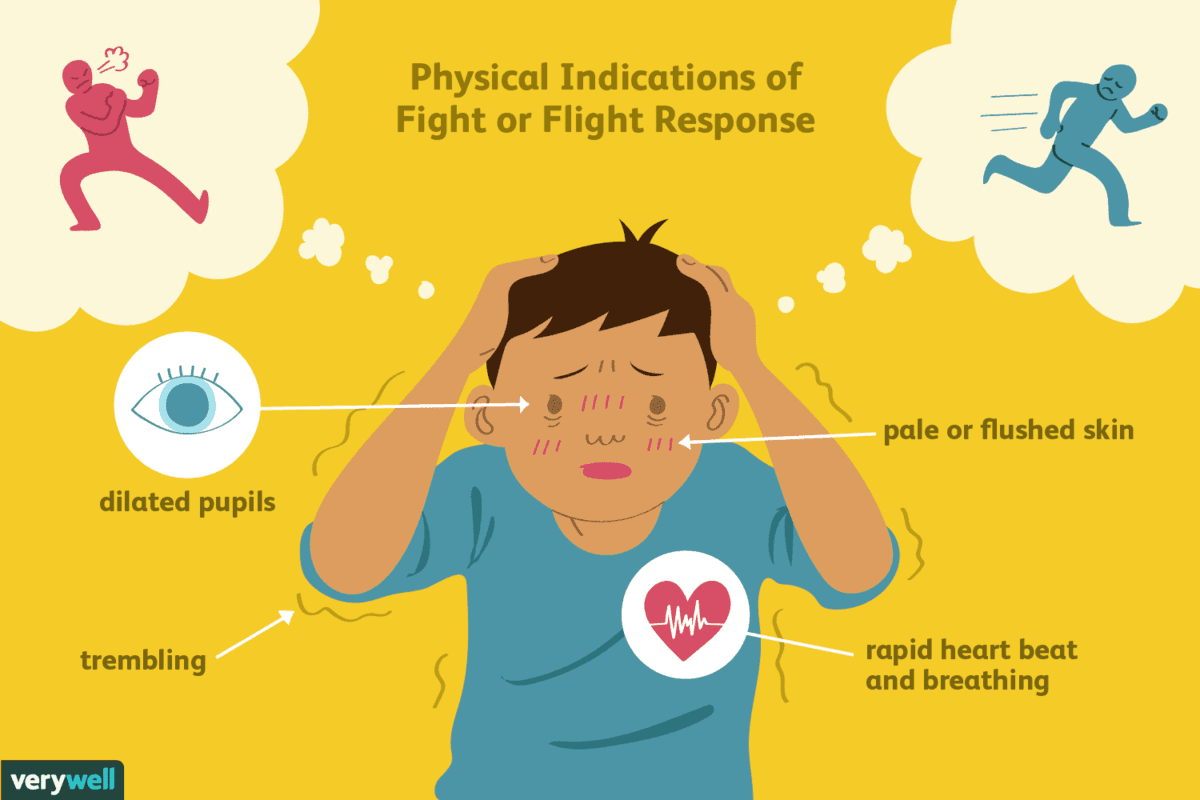

Moreover, the hunger hormone ghrelin is released whenever the body is exerting more than is consumed, and this is responsible for slowing the metabolism to conserve energy. Exercise and restriction increase adrenaline and cortisol levels, causing inflammation and the activation of the sympathetic nervous system, or our fight-or-flight mechanism. All these hormones slow the metabolism to conserve energy, meaning calories are used in the most efficient manner possible, allowing the body to run on fewer calories than it would need based on its size (Dooner, 2019). More calories are left unused and the body prioritizes storing calories as fat, regardless of its dietary fat content (Dooner, 2019).

What does all of this mean? Well, when you aren't taking in enough calories, your body makes storing calories as fat the top priority, "regardless of the dietary fat content of whatever you ate" (Mann, 2015).

These are all the ways our bodies try to protect us from starvation - we were programmed to survive - and explains why trying to manipulate your body weight outside of your set point weight is nearly impossible. As Traci Mann, author of “Secrets From the Eating Lab” puts it, “to maintain your [weight outside of its set point], you have to fight evolution. You have to fight your brain. You have to fight biology” (2015).

We are not discouraging individuals from trying to get to their “leanest livable weight,” and believe that adopting health behaviors should be encouraged, regardless if weight changes as a result. However, by understanding all the biological mechanisms that make living outside of your set point weight extremely difficult, we hope to highlight that the fight against our bodies and biology is not a fair fight. “You have to respect this miracle of being human, but you don’t have to like it” (Mann, 2015).

So, how do you know if you are within your set point weight? How do you find your healthy set point range?

Ask yourself: Has your weight remained within the same 5-10 pound range effortlessly (not giving food or exercise much thought) for over a year?

If you were to stop monitoring your food intake and exercise, where would your weight fall naturally?

The way you can determine your set point is by letting go of control over food and your body, and by instead tuning into your body’s natural cues for what, when and how much to eat. Instead of pushing yourself to exercise a certain way, intensity or duration, you may need to take a step back from exercise or engage in gentler forms of movement (Bates, 2019).

Works Cited

Bacon, L. (2010). Health at every size the surprising truth about your weight. Dallas: Benbella Books.

Dooner, C. (2019). The F*ck It Diet: Eating Should Be Easy. New York, NY: Harper Wave, an imprint of HarperCollins.

Ravussin, E., & Bogardus, C. (2000). Energy balance and weight regulation: Genetics versus environment. British Journal of Nutrition,83( S1). doi:10.1017/s0007114500000908

Mann, T. (2015). Secrets from the eating lab: The science of weight loss, the myth of willpower, and why you should never diet again.

Tomiyama, J., & Mann, T. (2008). Focusing on Weight Is Not The Answer To America's Obesity Epidemic. American Psychologist, 203-204. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.63.3.203